The news bulletin was orange with big gold lettering. Memory is dim concerning the exact wording, but it etched two things in my mind with permanent markers. A date. April 4, 1968. And an event that I intuited was historic based on my parents' reactions. Someone killed Martin Luther King, Jr.

I didn't know who he was, but I knew we weren't ever supposed to say his name in our house. I knew that because Keith said Mamma told Marie that. Marie didn't say anything but just kept ironing and humming as though it was the most natural mandate in the world. Their relationship was complex.

Dad once explained that the man was a troublemaker, which he often called me. He didn't like that I talked back, and I guessed that he thought the same of the dead man.

But he didn't say that when that orange bulletin interrupted Daniel Boone.

Urgency. Dad hollered for Mom to come see. She was washing dishes while we men watched TV. When Chet Huntley came on and told the world what happened, they seemed stricken. It was as though they knew we lost something precious that night because we desperately needed the trouble that troublemaker caused.

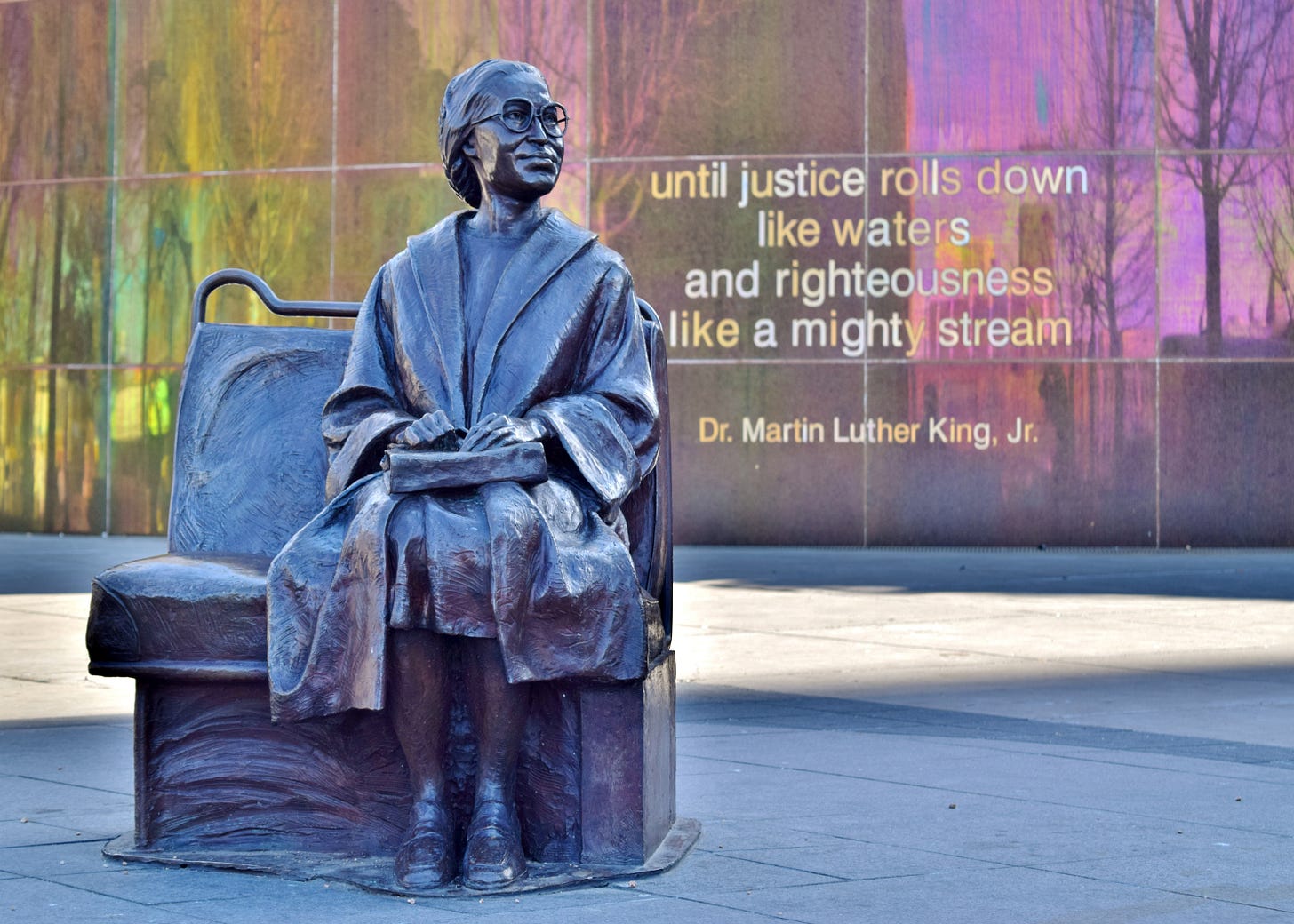

Late in life, I learned that he caused trouble by insisting Christians take seriously our baptismal promise to make Jesus's politics our own. A radical principle: we can't claim to love the neighbor we dominate.

I was able to audition for the youth production of Jesus Christ Superstar even though I didn't do youth group because the adults and teens knew me as their neighbor.

Things were different then. More connected. We teens grew up together.

My elementary school friends were my baseball teammates. My baseball teammates were also my Cub Scout den. Some of their dads coached; Mom was our Den Mother. Except for Doug, who was Roman Catholic, we also did Sunday School at Broadmoor Methodist, Baptist, or Presbyterian churches. Our mothers ran the Sunday Schools.

I got in trouble in second grade when I went to Broadmoor Baptist Church with Johnny Crutchfield. His dad coached the Broadmoor Baptist softball team. Mom permitted me to go. She got upset at learning that I answered the altar call and told the preacher I'd been "saved" so I could play second base for the Baptists.

In sixth grade, we walked from school to our respective churches so the Methodists and Presbyterians could be confirmed and the Baptists could be saved. Like trick-or-treating, we had no fear because the neighborhood moms were like aunts, benevolently ruling us and escalating things to our mothers if we got out of line.

Mrs. Roberts knew me because I visited her house weekly for Scout meetings. Kevin was my first patrol leader. Greg and I had been in the same Sunday School class since birth.

I had a lifelong crush on Mrs. Roberts. Only Julie Andrews outranked her. Mrs. Roberts went to LSU with Mom.

Things were different then. Except for those from Michigan who immigrated in droves after the '73 oil crisis, kids grew up together. Moms knew us, and we knew the moms. Trust was easier then.

So, when Dr. McQuire preached about loving our neighbors, that wasn't an abstraction. We knew our neighbors. They were the White middle-class families who surrounded us and ran things in Baton Rouge.

Not everyone counted as a neighbor.

Today, neoliberal capitalism is transforming the world, building global cities where laborers enter and exit daily without the possibility of citizenship rights. As in ancient Rome, only the elite are eligible to become citizens. Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Singapore, Honduras, Dubai, Qatar. Models of capitalist efficiency where laborers work during the day and leave at night, always aware they lack the political power to address grievances. Like ancient day laborers, they work when market conditions favor employment and go hungry when they do not. Their lives depend completely on the whims of the citizens who alone possess dominative power.

Scholars credit 1980s neoliberals like Milton Friedman with the invention of these features of global capitalism. But it's merely a derivative of everyday life I witnessed in southeast Baton Rouge during the 1970s.

Each day, our population would swell with the arrival of Black maids. Sometimes, they drove old cars, but eventually, city buses transported them near enough to walk a few blocks to their employer's home. At day's end, they'd return to their side of town.

Mom drove Marie home. She'd pile us into the station wagon and drive northwest toward the Mississippi River until we reached neighborhoods nearest the Exxon and Dow plants, where Marie and her large family had a house that seemed the size of our kitchen.

Later, Mom dropped off Marie at a larger house in a nicer area further from the chemical plants that lined the Mississippi River. They called it Section 8 housing. The first day we took her home, she proudly gave us a tour. I noticed Marie took care of lots of Mom's old stuff. That made me happy.

Mom and Marie had a complicated relationship. They cared for each other from their parenting phase to their golden years. Yet neither could look the other in the eye as equal neighbors do.

Dr. McGuire preached about our duty to neighbors often. Unlike Martin Luther King, Jr., no one called him a troublemaker. For our sanctuary had secure walls. We knew our neighbors. We grew up together.

As a kid, I never learned what Jesus said about people who didn't count as neighbors. Who weren't allowed to live in our neighborhood or stay after dark. Who lived across town in houses that looked nothing like our own. Like Marie.

Asked Dad about the folks who aren't our neighbors. Said, "I know about us. But what about them?"

Dad called me a troublemaker and didn't answer.