05: Mining Quantitative Christian Nationalism Data

In What is a Christian Nationalist?, I suggested that White-Christian Nationalism should be conceived as a hyphenated term because, empirically, the sociopolitical phenomenon is neither White nor Christian. Instead, it is a disordered politics practiced by a subset of the community whose social identity and cooperation arise from mutual subscription to the Anglo-Protestant ethno-tradition. I noted that, in 2023, the community includes persons of all colors, a plurality of non-Protestant Christians and non-Christians.

How do I know these things? They’re demonstrated in the prolific academic and popular work of sociology scholars whose field is known as Quantitative Christian Nationalism (QCN) research.

In response to the increasing polarization of American society, especially after the election of Donald Trump, a rapidly growing thread in social science and journalistic research focuses on American Christian nationalism. Andrew L. Whitehead, Samuel L. Perry, and others have pioneered QCN research. They have published a growing body of scholarly and popular books, articles, podcasts, and panel discussions that raise the alarm about a rising tide of American Christian Nationalism. The political left boosts QCN scholars’ work in the media aggressively because at its heart is the contested claim that Christian Nationalism causes a wide range of right-wing positions in America's culture wars.

At the heart of QCN research is the Christian Nationalism Scale, an index by which QCN scholars identify the probability of and intensity with which persons hold cultural and political views that QCN researchers associate with Christian nationalism. The scale is constructed by scoring survey respondents’ answers to six questions and adding the scores to compute an index value ranging from 0 to 24, from strong disapproval to strong support for Christian Nationalism.

QCN researchers deploy separate statistical models of political and cultural attitudes against the scale to demonstrate that higher Christian Nationalism scores predict right-wing responses to an ever-growing range of culture war questions, including support for Trump, racial equity, and gun, gay, and gender rights. They conclude that Christian Nationalism predicts such attitudes better than religious affiliation, frequency of church attendance, or political party. Most importantly, they claim that Christian Nationalism causes these right-wing political behaviors.1

It’s important to note that the six scored questions were not designed to measure Christian Nationalism. On the contrary, QCN researchers created their scale by redeploying scale items originally deployed to capture Americans’ views on the separation of church and state by a Baylor and University of Chicago study.2 That explains the absence of any mention of Christian Nationalism in the questions scholars use to classify respondents as Christian Nationalists.

I’ll signal here something I will unpack in a future article: I am skeptical of the helpfulness of the Christian Nationalism Scale in understanding the phenomena it purports to explain, and especially of how it has been used in the public square. The critique I will make downstream is that those who use the scale make empirical and analytical moves that fail to make essential distinctions, thereby putting too many Americans in the Christian Nationalism bucket.

QCN researchers’ key - and I think their weakest - methodological move is to assume respondents’ attitudes about the separation of church and state accurately predict the presence of Christian Nationalism. I mention this because the vast majority of accounts of Christian Nationalism are based on sociological work by Philip Gorski, Andrew Whitehead, Stephen Perry, and their collaborators, and so the biases of their methodology drive popular descriptions and shape many Americans' understanding of what an American Christian Nationalist is. It’s easy to read their popular books and walk away with the impression that anyone on the political right is either a conscious or unconscious Christian Nationalist and, indeed, their political behavior is caused by their Christian Nationalism. I am convinced there is no monolith at work here. We need to make careful distinctions.

Survey participants were asked to answer six questions with the prompt, “To what extent do you agree or disagree…” They could respond that they strongly disagree, disagree, undecided, agree, or strongly agree. Here are the questions:

1. “The federal government should declare the United States a Christian nation"

2 "The federal government should advocate Christian values"

3 "The federal government should enforce a strict separation of church and state"

4 "The federal government should allow the display of religious symbols in public spaces"

5 "The success of the United States is part of God's plan"

6 "The federal government should allow prayer in public schools"

Generally, QCN researchers divide the 24-point Christian Nationalism scale into quartiles, labeling them Rejectors, Resisters, Accommodators, and Ambassadors. They claim that the most supportive group, Ambassadors, who score from 17-24 on the scale,

“believe that the United States has a special relationship with God, and thus, the federal government should formally declare the United States a Christian nation and advocate for Christian values. Ambassadors support returning formal prayers to public schools and allowing the display of religious symbols in public spaces.”3

From a quantitative perspective, this is QCN researchers’ definition of a Christian Nationalist. Note that this definition says that a Christian Nationalist invites the government to privilege the Christian ethno-tradition. Still, it is silent on who counts as an American or a citizen. We shall see downstream that other definitions focus on who counts as a ‘real American.’

With those preliminary observations, let’s dig into the QCN data. The data below can be found in Whitehead and Perry (26-29).

A Summary of QCN Survey Data

52% of Americans agree with all or most questions QCN researchers use to categorize individuals as Christian Nationalists.

88% of this 52% identify themselves as white evangelical Protestants

Only 13% of Black and 33% of all persons of color scored in the top half of the Christian Nationalism scale.

55% of respondents’ scores mark them as the most passionate adherents, and, of these Ambassadors:

White evangelicals (55%), Catholic (19%), Mainline (11%), Black Protestant (10%)

55% are women

50% live in the South and 21% in the Midwest

70% are white

The mean age is 54

93% did not graduate from college

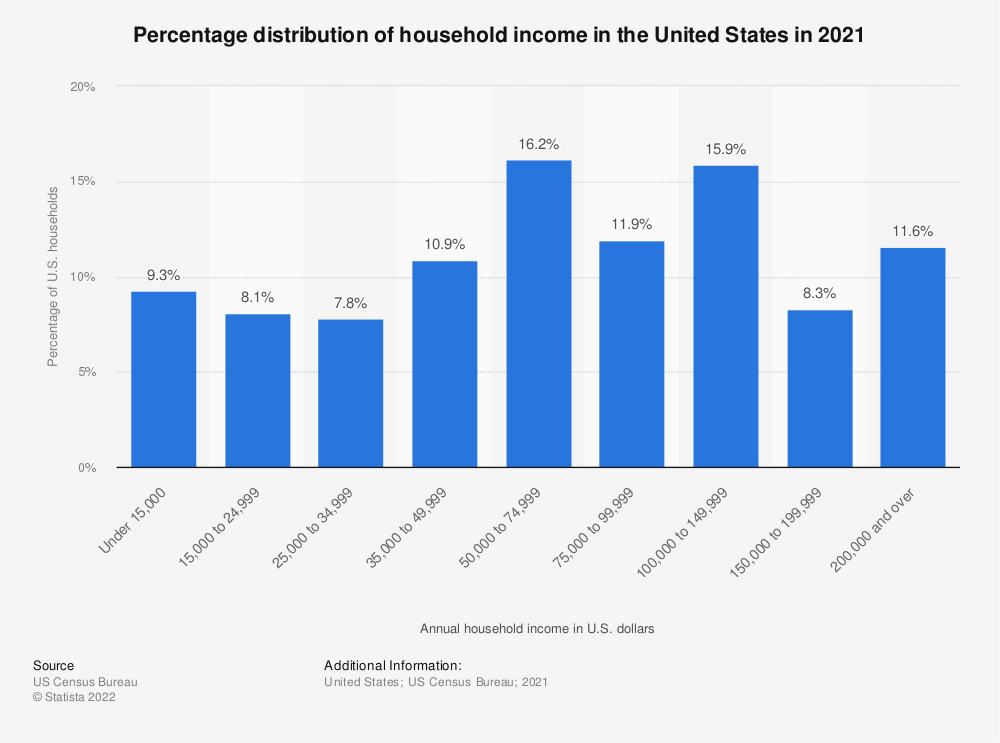

56% have household incomes less than $50,000

Among the 32% who scored in the 12-17 range on the 24-point index (the Accommodators):

White evangelicals (33%), Catholic (32%), Mainline (12%), Black Protestant (9%)

57% are women

39% live in the South, and almost 28% live in the Midwest

63% are white

17% have college degrees

54% earn household incomes less than $50,000

23% earn household incomes less than $20,000

A Few Data-Driven Observations

Whiteness is the Key

QCN researchers claim that the Christian Nationalism scale accurately predicts respondents’ views on various policy questions regarding race, discrimination, immigration, xenophobia, and justice. Those who score highest on the Christian Nationalist scale do not support government policies aimed at lifting the poor, welcoming the resident alien, or eliminating social barriers based on race or gender. As Episcopal Church Presiding Bishop Michael Curry noted, this suggests that their politics are ordered based on criteria other than those taught by Jesus.4

In contrast, those on the bottom half of the scale (Rejecters and Resisters) support such policies.5

Interestingly, 25% of Blacks either accommodate or passionately support Christian Nationalist beliefs, indicating they value the White-Christian ethno-tradition despite its habits of exclusion and think highly of the role of Christianity in our national politics and governance. One might think their high scores - identifying them as Black Christian Nationalists - would predict that their expectations concerning discrimination and their preferences for public policy would mirror those of White Christian Nationalists. That’s not the case, however. Black Ambassadors and Accommodators share expectations concerning racial discrimination and preferences for public policy with their Black Resisters and Rejecters. The intersection of one’s Christian Nationalism score and race, not one’s Christian Nationalism score alone, predicts one’s public policy preferences. To extend Bishop Curry’s logic and language, per QCN research, Black Christian Nationalists align their politics with Jesus, but White Christian Nationalists do not. Identification as white is the key.

The Exploitation of Poor Whites

The QCN data reveal another characteristic that heightens ethical concerns and provides insight into potential responses to this phenomenon. Those who score in the top quartiles of the Christian Nationalism scale are predominantly the least economically privileged American citizens. Indeed, those with household incomes less than $50,000 disproportionately score higher on the Christian Nationalist scale, including 56% of Ambassadors and 54% of Accommodators. In contrast, those earning household incomes less than $50,000 constitute only 36.1% of the U.S. population. This puts into sharp relief the $250 entrance fee demanded and merchandise sold by promoters of the ReAwaken America Tour, other organized religio-populist gatherings, as well as current efforts to pay Trump’s mounting legal fees by fund-raising schemes that target these quartiles. These are phenomena in which the most economically privileged in the population actively call the least privileged into a religio-populist movement parodying America’s two Great Awakenings that displays characteristics of both sect and cult, transfers wealth from the poor to wealthy evangelists, generates political power for those evangelists, and promises salvation to the poor based on their blood sacrifice.

These 21st-century spectacles through which elite White businesspeople cultivate an alliance with low-income Whites through the unashamed affirmation of White Supremacy evoke a tragic bargain in American history. Shortly after the passage of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments and the collapse of Radical Reconstruction, hope that we would achieve the promise of those amendments remained due to a new alliance between Black and White farmers. This populist movement based on shared socioeconomic concerns of poor farmers lasted well into the 1880s. Planter-class Whites, faced with an extreme labor shortage arising from the emancipation of enslaved workers, broke the alliance by actively cultivating relationships with lower-status White farmers. They proposed that poor Whites secure their participation in the social, economic, and political fruits of a new post-Reconstruction social order in exchange for their political cooperation with elite Whites. As explained in our podcast, How and Why We Birthed Jim Crow, the new race-based coalition gave elite Whites an enduring majority, enabling the passage of the Jim Crow laws that ensured the commodification of Black labor for another century.6

As in the 1880s, the 21st-century bargain is a great business for the elite White sponsors of Christian Nationalist events like the ReAwaken America Tour. They exploit poor Whites economically and obtain political leverage enabling them to shape public policy that generates riches for their patronage networks.

But what do less privileged Whites obtain in exchange? Sociologists tell us it’s not about economics. The primary good obtained is the promise of protection from ethnic change from immigration that, as Eric Kaufman notes, “unsettles the existential security of conservative and order-seeking whites.”7 The insecurity is less about economics and more about preserving status and social respect: “Well, I may be poor, but at least I’m not Black.”8 On this account, less privileged Whites embrace White Christian Nationalist religious ritual, rhetoric, and political allegiance in exchange for the this-worldly goods of respect, security, and fellowship in response to existential threats from ethnic change.

Let me re-frame this last observation so we may more readily connect it with concepts we will develop downstream. Less privileged Whites place their faith in an account of human flourishing grounded in the normativity of the Anglo-Protestant ethno-tradition based on the promise that such an ultimate concern will provide this-worldly rewards like status, security, and fellowship. The next article considers how this plays out differently across the socioeconomic spectrum.