The Conversation That Changed Everything

"Have you asked Craig if he's racist?"

The question from my wife's older brother Salin hung in the air between them. He was concerned about some of my Facebook posts discussing American history and racism.

When my wife later told me about this conversation, I felt a surge of indignation and outrage that I'm guessing might feel familiar to many of you reading this. How dare he? I thought. I've dedicated my life to bringing people together. I've actively worked against racism. I have close friends from diverse backgrounds. The accusation felt not just wrong but deeply unfair.

This defensive reaction—this immediate sense that I was being unfairly accused—is precisely the same feeling that many white Americans experience when confronted with discussions of systemic racism or our country's racial history. It's a reaction I now understand completely, because I lived it.

What changed for me wasn't being lectured or shamed. What changed was my gradual exposure to historical facts I had never been taught—realities about our shared American story that had been carefully edited out of the textbooks I studied and the historical narratives I'd absorbed.

As I began to discover these hidden chapters of our history, I realized that Salin's question wasn't an attack but an invitation to see beyond the partial history I had inherited. My outrage gave way to curiosity, and eventually, to a more complete understanding of both myself and our nation's past. Like measuring our personal growth or national progress, I had to reconsider what metrics truly matter in understanding our shared story—moving beyond defensive self-perception to embrace a more complete reality.

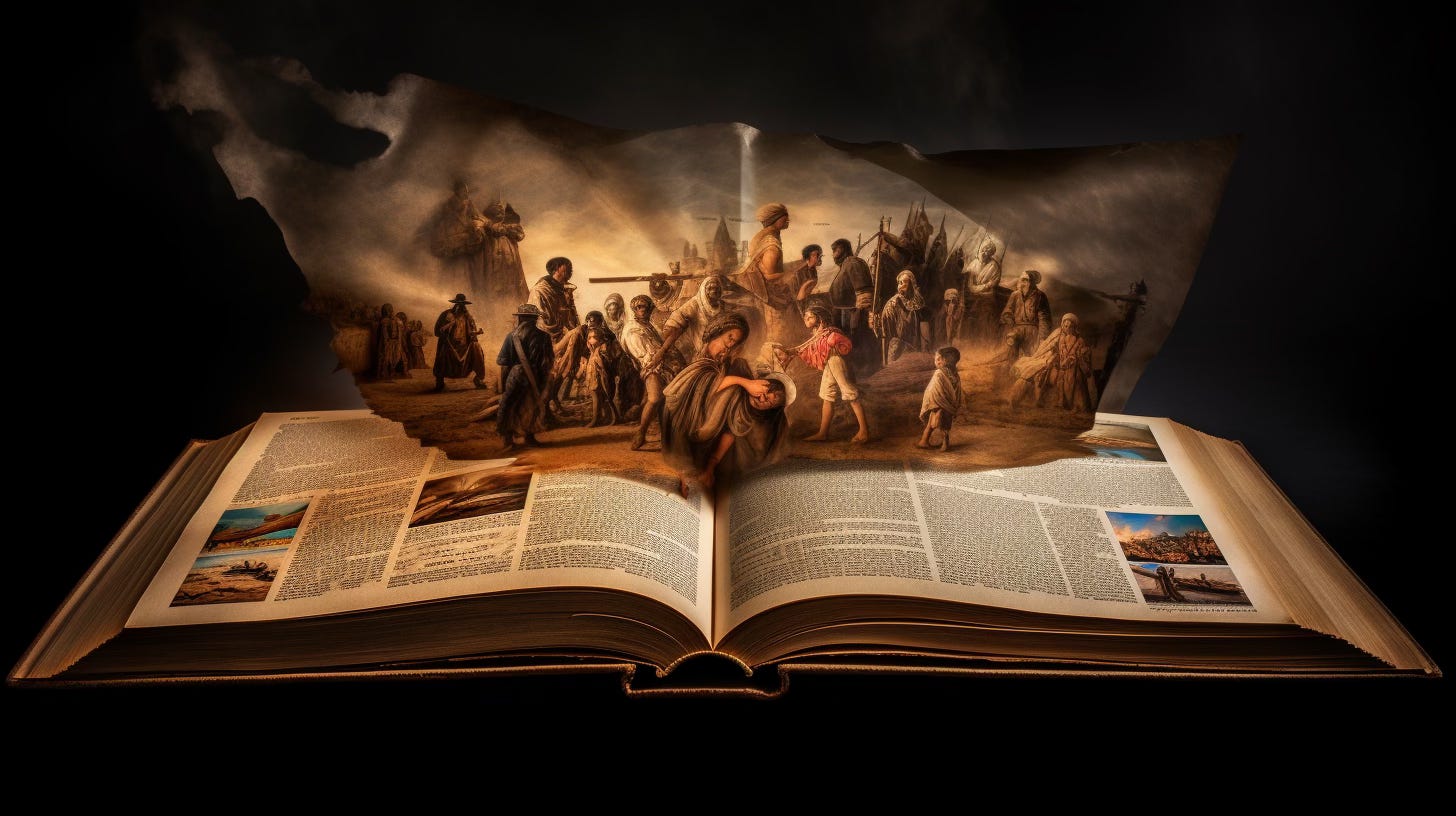

This series is my attempt to share that journey with you—not to induce guilt or shame, but to offer the same invitation I received: to discover a fuller, more complex, and ultimately more truthful story of America than many of us were taught.

The Myth of a Single Origin

I grew up with what I now recognize as the "single origin myth" of America—the comforting narrative that our nation began with the English Pilgrims at Plymouth Rock, expanded through heroic westward settlement, and gradually extended liberty to all.

This story wasn't a complete fabrication. The Mayflower passengers did arrive in 1620. English colonization did form a crucial thread in our national tapestry. But I've come to understand that this narrative functioned like those optical illusions where one picture contains multiple images—once you see the second image, you can never unsee it.

The "single origin" story I was taught didn't merely simplify—it systematically erased entire founding peoples and civilizations from our national consciousness.

The First Discovery: Spanish America

My journey began with Carrie Gibson's book El Norte, which revealed that by the time the Mayflower landed, Spanish America already had established settlements, universities, printing presses, and complex governance systems throughout what is now the American Southwest and Florida.

St. Augustine, Florida—the oldest continuously inhabited European settlement in the United States—was founded in 1565, more than half a century before Plymouth. Santa Fe, New Mexico followed in 1607, predating both Plymouth and Jamestown.

This wasn't just a matter of "who was first." It represented a fundamentally different understanding of what "America" was and is. Spanish America wasn't a separate history that happened alongside "real American history"—it was American history, just as integral to our national formation as the English colonies.

Why had I never learned this in school? The answer, I discovered, had everything to do with who gets to define what "American" means.

The Americas Before Europeans

The deeper shock came when I began to study indigenous civilizations that existed long before European arrival. These weren't the simplistic caricatures of my childhood education—"primitive" societies that conveniently faded into the background of the European story.

They were sovereign nations with complex systems of governance, extensive trade networks, sophisticated agricultural techniques, and rich cultural traditions. The Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy, with its democratic governance system that influenced our Constitution, had been thriving for centuries before European contact.

In what is now the American Southwest, Pueblo peoples had built multi-story apartment complexes, engineered sophisticated irrigation systems, and established far-reaching trade networks. The Mississippian culture had constructed Cahokia, a city larger than London at the time, with massive earthworks that still stand today.

These weren't peripheral stories to American history—they were foundational chapters that had been deliberately omitted from the narrative I was taught.

Not Just Who, But How Many

Perhaps the most profound shift in my understanding came from learning about population estimates. The textbooks of my youth portrayed a mostly "empty" continent with scattered indigenous inhabitants—a narrative that conveniently justified the idea of manifest destiny.

More recent scholarship suggests that between 50-100 million people lived in the Americas before European contact—with sophisticated civilizations throughout North America. Disease, often moving ahead of actual European settlement, decimated these populations, creating an illusion of emptiness that shaped European perceptions and policies.

This wasn't merely a demographic detail—it fundamentally changed my understanding of what European settlement actually meant. The "wilderness" being "tamed" was often land recently depopulated by pandemic disease, with ecological systems already shaped by thousands of years of human management.

The Disorienting Truth

These discoveries were profoundly disorienting. I felt a sense of betrayal that so much had been hidden from me, anger at the incompleteness of my education, and grief for the rich heritage that had been denied to all Americans through this selective telling.

But I also felt something unexpected: a growing excitement about discovering a more complex, truthful, and ultimately more interesting American story than the one I'd been taught.

This journey hasn't been about rejecting my heritage or embracing some simplistic "anti-American" narrative. Quite the opposite—it's been about claiming a richer, more complete American inheritance that belongs to all of us.

An Invitation, Not an Accusation

So this series is my invitation to you—to join me in discovering this more complete American story. Not as an accusation or an exercise in guilt, but as a journey toward a more honest reckoning with who we are and where we came from.

In the coming weeks, we'll explore:

The Spanish America that predated Plymouth

The indigenous nations that shaped our continent

The distinct regional cultures from Britain that created enduring American divides

The African civilizations and knowledge systems that built much of our nation

The Mexican Americans who never crossed a border (the border crossed them)

The Chinese laborers who connected our continent

And many more "untold" chapters of our shared heritage

This isn't about replacing one exclusive narrative with another. It's about expanding our understanding to include all the peoples who made America what it is today.

My hope is that like me, you'll find this journey not demoralizing but liberating—an opportunity to embrace a more truthful, more inclusive, and ultimately more hopeful American story than the one many of us were taught.

Next Thursday: "Beyond the Mayflower: The Spanish America That Predated Plymouth"

If you found value in this essay, please consider sharing it with others who might appreciate this journey. Your comments and perspectives are welcome—this is a conversation, not a lecture.