Dear friends,

Here’s the short version: achievement can’t heal shame because they operate at different levels of the nervous system. You’re trying to update software when the firmware is corrupted.

This essay traces how the body tells the truth about shame long before the mind can make sense of it, and why the kind of pride that actually heals can only grow once safety returns. If you’ve ever wondered why decades of achievement never quieted the shame, or why some pride feels generous while other pride feels brittle and defensive, this is the grammar beneath it.

The vocabulary gets technical in places—neuroscience carries its own jargon. But what matters isn’t whether you can decode every term. What matters is whether this names something your body already knows.

Two essays ago, I claimed shame was gift—the body’s way of calling us back toward communion we’ve disrupted. Last week, I confessed how my family taught me to construct identity through heroic service disguised as Christian virtue. Both essays were preamble to the claim I’ve been circling: achievement can’t heal shame because they operate at different levels of the nervous system. You’re trying to update software when the firmware is corrupted. It’s like debugging your email client when the motherboard is fried—technically impressive effort directed at the wrong level of the system entirely.

This is going to require some vocabulary—neuroscience has its lexicon, after all. But Stanley Hauerwas drilled this into me at Duke: what matters isn’t comprehension (can you decode the terms?) but intelligibility (does this make sense within the Christian grammar you already inhabit?). If you can’t translate neuroscience back into the language of creation, fall, and redemption, it’s just expensive trivia. (And if your theology can’t account for what neuroscientists have discovered about how shame actually works in bodies, it’s not theology—it’s spiritual fantasy poorly disguised as doctrine.)

I’m not a neuroscientist—which is precisely the point. Theology doesn’t master other disciplines; it locates them inside larger stories, bringing theological wisdom to bear without pretending expertise it lacks. What follows is theological interpretation, not scientific discovery: listening to what researchers have learned about shame and pride in actual bodies, then asking what it means if those bodies were designed for connection, know the pain of rupture, and can be restored through sustained presence. The neuroscience names mechanisms. Theology names meanings. My hope is that you’ll find yourself thinking not “This is too technical” but “Oh—this names something I’ve lived but never had words for.

Story Follows State

Nobody told you the truth about feelings—that they arrive in sequence, body-to-mind, not mind-to-body. We treated ‘feelings’ like spiritual weather, something character determines: strong people feel less, weak people feel more. The whole edifice was moralized ignorance.

When someone says “you’re overreacting,” they’re committing a category error so fundamental it would be funny if it weren’t tragic. They’re treating your body’s involuntary threat response as if it were a seminar paper you could have revised. As if the fire alarm screaming in your chest were subject to parliamentary procedure. The phrase “you’re being too sensitive” is theological malpractice dressed up as pastoral care—demanding that bodies pretend they’re not bodies, then blaming them when biology refuses to comply.

Here’s what nobody told you: story follows state. The mind arrives last—always.

Which means every time you’ve tried to think your way out of shame, you were attempting the neuroscientific equivalent of time travel. The body had already decided, the nervous system had already arranged itself, and consciousness was just arriving with its interpretive commentary, fashioning explanations for events already underway. You can’t narrate yourself out of what fired before narrative existed.

The sequence is hardwired: affect (biological flash in milliseconds), emotion (body’s arrangement—breath rhythm, muscle tension, facial expression), feeling (awareness of that arrangement), story (mind’s attempt to explain what already happened). Tomkins called affect the “biological portion of emotion”—the hardwired response that precedes everything else. Affect fires instantly. Story constructs slowly. And most of Christian formation operates at the story level, trying to narrate people into different nervous systems.

This is why that micro-expression in someone’s face can hit you before either of you has a thought. Their body registers a break in connection. Yours registers that registration. Two nervous systems answer one another long before either person knows what they are answering.1 You interpret the shift as an indictment—a moral failure in you or in them. But the story you tell is simply the narrative your mind constructs to match the physiological state you’ve already entered.

Once you see this order, you understand how often we treat a body’s reflex as a character issue. We call it “overreacting,” “being too sensitive,” “not handling things well,” when the body was simply signaling, “Something between us cracked—come closer.”

It wasn’t character. It wasn’t intention. It wasn’t even “emotion” in the way we were taught to think of emotion. It was state. And the story we attach to that state—our defensiveness, our assumptions, the courtroom we build in our heads—is downstream of a biological sequence no one chose.

The mind is not the captain steering the ship. It is the breathless narrator sprinting after the body, trying to explain whatever direction the organism has already turned.

This is what it means to say story follows state: not that story is unimportant, but that it is never the beginning of the truth about us. It is the last arrival at a scene the body has already entered.

A few weeks ago, I explored how shame itself functions this way—not as a moral verdict but as the body’s first punctuation mark when connection cracks. Rightly ordered shame is a signal: “Something between us broke—come closer.” Disordered shame is what happens when that signal metastasizes into identity: “I am the break. I am defective. I am the problem.” This distinction matters because when shame is a semaphore it calls us into true stories from which rightly ordered pride emerges, but when shame becomes a verdict it enmeshes us in false stories from which hubristic pride grows.2

Safety, Unsafety, and the Body’s Silent Radar

Neuroscientists have a word for what your body is doing long before you have a thought about a situation: neuroception—the nervous system’s silent radar.

It is always scanning for three basic conditions: Am I safe? Am I in danger? Am I under threat? And it answers before emotion and long before thought.

This is why a tiny change in someone’s tone, or a sudden quiet in a meeting, can feel larger than the moment itself. The body isn’t asking, “How should I interpret this?” It’s asking the more primal human question: “Are we okay?”3

When the nervous system senses yes—when the relational field feels intact—the face is open, the voice warm, the breath steady. Safety shows up as accessibility, responsiveness, and ease. When the nervous system senses no—even slightly—everything tightens. Unsafety is felt as: I might be excluded, I might be in the wrong, I might be too much, I might be alone in this moment.

You see this in ordinary places: a coworker’s expression goes flat in a meeting, a friend replies with a brief text after a long exchange, someone’s tone shifts on a call, a group falls quiet when you walk into the room. No one chose a reaction. No one chose a story. The body registered something first and prepared itself.

And because we grew up with the wrong map, we often treat these reflexes as evaluations—as if someone were judging us, or as if we had failed in some way—when the nervous system is simply alerting us that something in the relational field needs attention. The body wasn’t declaring a verdict. It was raising a small signal: “Something shifted—check the connection.”

This is the safety/unsafety axis. Not a moral scale, not an emotional scale, but an attachment-detection system trying, beneath awareness, to answer the oldest human question: Are we okay?

The Nervous System as an Ensemble

The human nervous system didn’t arrive all at once. It evolved in layers, each repurposing older circuitry for newer forms of life. Stephen Porges gave us a way to hear this architecture beneath our reactions—but not as floors we move between. Instead, think of it as an ensemble where three sections are always playing simultaneously, competing for dominance.4 This isn’t sequential activation—all three broadcasts run constantly. What changes is which signal achieves hierarchical dominance in that moment, modulating the others’ influence without silencing them.

Two weeks ago, I described the jazz musician who drops the beat. Face flushes. Chest tightens. The shame affect triggers. And in that micromoment, three responses fire at once:

Stop playing altogether—freeze, withdraw, disappear from the ensemble. This is the dorsal vagal response: the ancient reptile circuitry that shuts down when overwhelmed.

Blast louder, drown everyone else out—Attack-Other disguised as confidence, make sure no one can ignore the mistake by covering it with volume. This is the sympathetic response: the early-mammal circuitry mobilizing to fight, flee, defend.

Stay with the band, listen harder, find the downbeat—adjust, breathe, return to the groove. This is the ventral vagal response: the advanced-mammal circuitry that lets us connect, co-regulate, and stay present.

All three are active. All three are broadcasting. The question isn’t which circuit you’re “in”—it’s which one wins dominance in that moment. Under strain, the sympathetic or dorsal broadcasts drown out the ventral signal. Under safety, the ventral broadcast becomes clear enough to stay in the ensemble. But all three are always playing, competing for control—not taking turns.

This is the architecture beneath shame and pride. When shame fires—that instant biological flash signaling broken connection—the competition intensifies. The dorsal impulse says disappear. The sympathetic impulse says dominate. The ventral impulse says listen, adjust, return. Which one dominates determines whether shame does its healing work or becomes toxic.

Healing pride requires the ventral signal to stay strong enough that the nervous system can interpret agency truthfully. Authentic pride can only grow when the ensemble holds—when shame can be received as semaphore rather than sentence, when we can participate freely without performing our worth.

This is why achievement can’t heal shame. Achievement operates at the cognitive level—building new pride through effort and validation. Shame operates at the pre-cognitive level—registering rupture before thought. You’re trying to solve a firmware problem with software updates.

I spent decades attempting this impossible project. Naval Academy. Nuclear submariner. High-tech company president. Duke and Durham theological degrees. Published books and essays. The achievement was real. The validation was real. But the healing? That never came. Because I was working at the wrong level of the system entirely. You can’t think your way out of what fired before thought existed.

This is what I couldn’t see in the “be the gift” formation I described last week—the Christianized Stoicism that taught me to construct worth through performance. That entire system operated from sympathetic circuit dominance dressed up as virtue. No amount of achieving could restore the ventral circuitry that would have let me receive love in the first place. I was trying to heal connection wounds with achievement tools, blasting louder to cover the shame instead of listening my way back to the ensemble.

And here’s what makes hubristic pride so insidious: it’s what happens when the sympathetic broadcast dominates and the mind mistakes that arousal for confidence, for certainty, for righteousness. You’re still in the band, technically—but you’re drowning everyone else out. Authentic pride is what happens when the ventral signal holds clearly enough that you can play your part without silencing the others.

This ensemble is the backdrop for everything that follows.

What Sadie Knows That We Forgot

My wife and I often remark on how Sadie, our Goldendoodle, reads us. She knows when one of us is sad—not by what we say, but by what our bodies broadcast. She’ll watch from across the room, head tilted, and then pad over quietly, pressing her body against a leg or resting her chin on a knee. She doesn’t fix anything. She doesn’t solve anything. She just offers her presence, her warmth, her steady breath. My wife calls it Sadie’s ministry. I call it uncanny.

Here’s what makes it uncanny: Sadie can read me even when I’m working hard to hide what I’m feeling. My Stoic training runs deep—I can keep my face neutral, my voice even, my posture controlled. I can fool my wife on a bad day. But I can’t fool the dog.

Sadie doesn’t read thoughts. She reads bodies—and specifically, she reads right-hemisphere signals that bypass conscious awareness.5 This is the original language of attachment, operational before words and deeper than words. Emotion is not primarily happening in the mind. It’s happening in the body—in breath rhythm, muscle tension, micro-expressions, the barely perceptible shift in how you hold yourself. The mind narrates what the body has already broadcast. Sadie knows this because dogs live closer to the truth than we do. They haven’t learned to ignore what the body says.

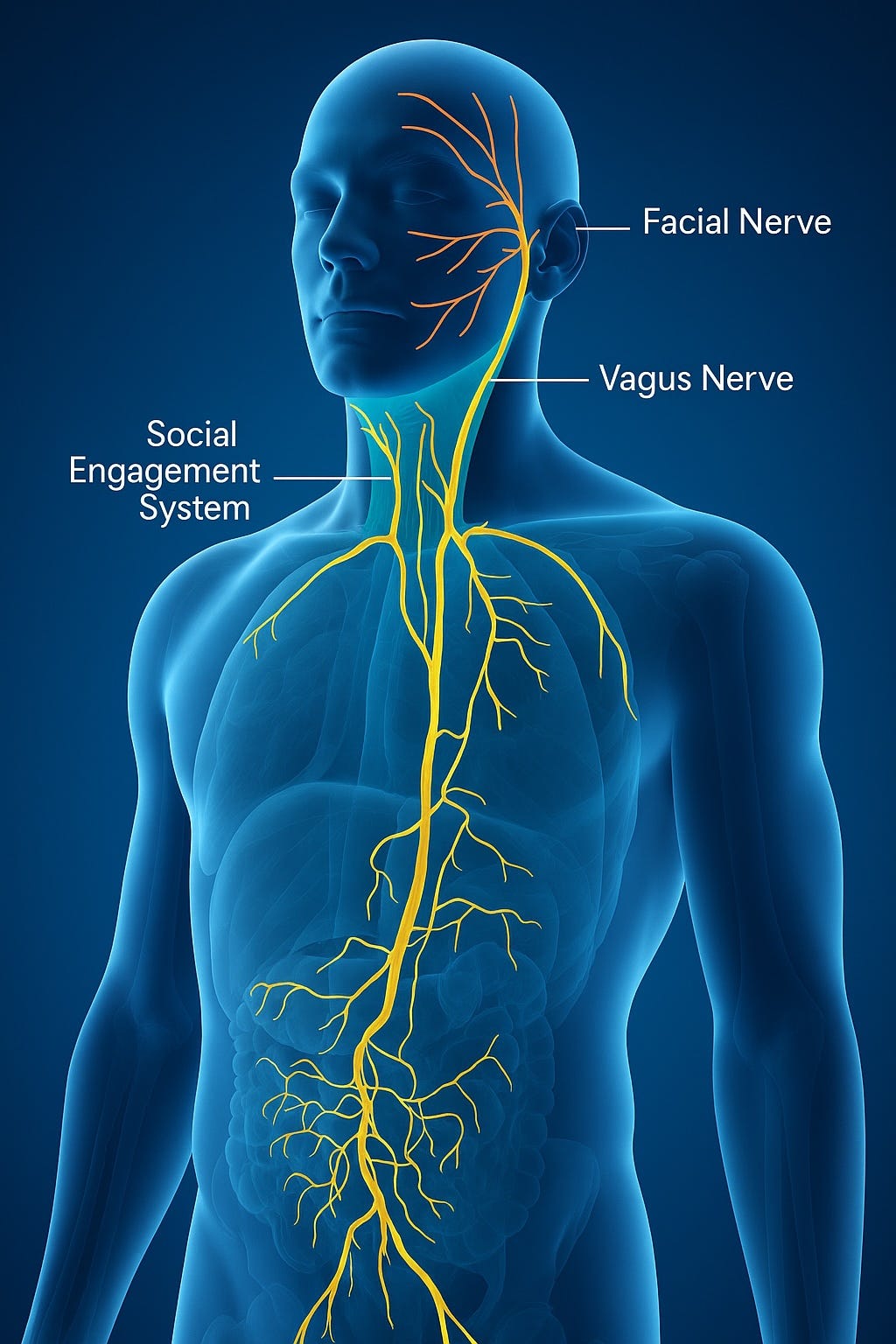

What Sadie is reading—what all mammals read in each other—is the nervous system’s state. And that state is wired through structures most of us have never seen but that shape our daily lives more than anything happening in the brain. This is not metaphor; it is anatomy—the actual wiring through which human beings feel safe, threatened, connected, or alone.6

The facial nerve (typically shown in orange in anatomical diagrams) governs the muscles around the eyes, mouth, and voice. This is why safety shows up in soft eyes, warm tone, relaxed facial expression—and why threat appears in tightened mouths, sharpened eyes, clipped voices. Your face is not decoration; it is your nervous system’s front porch. Sadie reads that porch before I know I’ve changed the welcome mat.

The vagus nerve (typically shown in yellow) runs even deeper. It stretches from the brainstem through the throat, heart, lungs, diaphragm, and into the gut. When people say “my heart sank,” “my stomach dropped,” “I felt it in my chest,” they are not speaking symbolically. They are describing neurobiology.

The upper branch of the vagus links to the face, voice, and hearing—tuning you to another person’s presence. The lower branch runs through the chest and abdomen—carrying signals that tell you whether to settle or brace. This is why relational rupture feels bodily: chest constriction, shallow breath, a knot in the stomach. The system contracts because it has sensed a change in the relational field.

And this is why connection feels bodily too: a loosening in the chest, a widening in the breath, a gentler voice, a felt sense of being able to stay. Sadie knows when those signals shift—when the chest loosens, when the breath deepens—and she stays until they do.

Stephen Porges calls this whole network the Social Engagement System—the integrated organ of face, voice, breath, and heart that allows two nervous systems to meet each other.7 When this system is online, co-regulation becomes possible. When it drops offline, the older survival circuits take over. Sadie is a co-regulation specialist. She lends her steadiness until ours returns.

Here is the key: your nervous system experiences your relationships before your mind can name them. Your face reacts before your feelings. Your gut reacts before your thoughts. Your heart reacts before your story. Sadie taught me this before any neuroscientist did.

This is why the Christian tradition has always insisted that we are embodied creatures, not minds floating above our flesh. “Heart” and “gut” were not metaphors for the ancient world; they were wise descriptions of where truth is actually felt.

Neuroscience now shows what the tradition intuited—and what Sadie practices daily: grace is something the body recognizes before the mind understands. The gentle pressure of steadiness. The widening of breath. The slow discovery that we have been found. Grace is God’s act. The body feels that act in its own language. Sometimes that language is a Goldendoodle pressing her warmth against your leg until the ventral circuitry comes back online and you remember you’re not alone.

The River That Widens and Narrows

One of the most illuminating ideas in the last twenty years of psychology is what Dan Siegel calls the window of tolerance—the range in which the nervous system can stay present, flexible, and connected under stress.8 Inside this window, we can think and feel at the same time. We can tolerate difference. We can repair ruptures. We can stay in the room. This isn’t just metaphor—it’s physiologically trackable. We measure its correlates through heart rate variability, respiratory patterns, vagal tone, and other autonomic markers that show when the system is regulated versus dysregulated.

I started tracking this personally when I was training for marathons—strapping on my Polar heart monitor each morning to check whether my parasympathetic nervous system was recovering from training stress or still depleted. The numbers told me when to push and when to rest. Now I use the same metrics as a window-of-tolerance monitor. When my HRV drops, I know I’m vulnerable to responding as a reptile or lower-order mammal rather than the homo sapiens my wife married. Sympathetic hijack is one bad meeting away. The river has narrowed, and I need practices that widen it again before attempting anything requiring nuance, empathy, or staying in the room during conflict.

But the “window” behaves more like a river than a rectangle. A river widens when conditions are good: rest, connection, predictability, repair, attuned presence. In a wide river, disturbances are absorbed gently. We have room for nuance, patience, curiosity.

The river narrows when the weather changes: fatigue, chronic stress, accumulated emotional labor, unprocessed shame, relational strain, loss. When the river is narrow, even minor disruptions feel overwhelming. It isn’t fragility; it’s biology under strain. A narrow river can overflow fast.

You see this every day. A parent operating on broken sleep, their window already narrow before the day begins. A clinician, pastor, or teacher carrying the weight of others’ crises, metabolizing trauma that isn’t theirs to carry. A colleague stretched thin after weeks of unresolved pressure, smiling through meetings while the river shrinks. Anyone living with ongoing grief or shame, where yesterday’s losses narrow today’s capacity. People managing hidden emotional labor in family systems or workplaces—the ones who smooth everyone else’s rough edges while their own margin disappears. Each of these people begins the day with a river already low. Their capacity hasn’t vanished; their margin has.

Outside the river—above it in sympathetic mobilization or below it in dorsal collapse—everything changes. We stop hearing nuance. We lose access to empathy. We misread neutral faces as threat. We speak sharply or withdraw suddenly. We interpret our body’s distress as personal failure or someone else’s fault. What looks like “overreaction” from the outside is often just the nervous system slipping out of its river.

This is why exhortations like “try harder,” “calm down,” or “just let it go” rarely help. Exertion cannot widen the river. Only co-regulation and renewed safety can.910

When someone lends us steadiness—a calm presence, a grounded voice, a furry head, a non-judging face—the river widens again. Breath deepens. Muscles release. Perspective returns. We become capable of connection. This is the river at the heart of human life: the flowing range within which communion is possible.

What narrows it? The burdens we carry in our bodies. What widens it? Presence, safety, repair, and love.

How the River Widens

When the nervous system slips out of its river—upward into agitation or downward into collapse—most of us try to “handle it” on our own. We grit our teeth, brace our bodies, tighten our breath, push through. But biology is stubborn: exertion does not widen the river. Regulation does, and regulation is almost always relational.

Humans developed an entire network for this—the system Stephen Porges calls the Social Engagement System. It links the muscles of the face, the tone of the voice, the rhythm of the breath, the steadiness of the heart, even the small muscles of the middle ear that tune us to another person’s voice. These are not poetic images; they are anatomical pathways built for one purpose: to help nervous systems find one another.11

When that system is online—when someone near us is steady, open-faced, warm-voiced—our own body begins to match it. Breath slows. Shoulders drop. The jaw releases. Our chest loosens. Attention returns. We regain access to nuance, empathy, curiosity. The river widens.

This happens in ordinary moments: a friend stays grounded while we are overwhelmed, and our breath settles; a colleague speaks gently in a tense meeting, and the room softens; someone listens without rushing to fix, and our body begins to unclench; a caregiver kneels to meet a child’s eyes, and the child’s panic melts. No one solves anything in those moments; they simply lend their regulation, and our nervous system receives it—often before we realize anything has changed.

Co-regulation works through neural synchrony—when one mammal’s nervous system maintains regulated state, it literally entrains another mammal’s autonomic rhythms through shared gaze, vocal prosody, and physical proximity.12 This happens primarily through right-hemisphere-to-right-hemisphere communication—nonverbal, subcortical, body-to-body.13 Before words can help, bodies must find each other.

This is why co-regulation is not a sentimental idea but a biological reality: your nervous system was designed to borrow steadiness from another mammal until your own can come back online. The older Christian grammar has always intuited this. “Presence,” “withness,” “abiding”—these are not abstractions but describe the creaturely way grace is mediated: one person staying present enough that another can find safe ground again.14

This is why the river widens not through self-rescue but through received presence. And once the river widens, we can tell the truth about what is happening in us. We can reconnect. We can choose differently. We can return to one another. Co-regulation is not a technique; it is how communion begins again.

Grace as Neuroception

There is a reason the Christian tradition has always spoken of grace as something we receive before we understand it. The body knows what the mind is slow to name. Grace arrives first as a change in state—a softening, a widening, a settling—long before it becomes a doctrine or a story.

This is what neuroscience makes newly visible. When the nervous system feels safe enough to stay open—when the ventral circuitry holds—the body can tell the truth about itself again. Fear loosens. Breath deepens. The jaw unclenches. The chest releases. The field between us feels less dangerous, more spacious. The body recognizes something before the mind can narrate it:

“I am held.

I am not alone.

I can stay.”

The First Letter of John says it like this: “Perfect love casts out fear” (1 John 4:18).

For most of my life, I heard that as a metaphor. Only recently have I seen that it also names a physiological event.

Fear belongs to the early-mammal circuitry—the sympathetic engine built for threat vigilance (phobos). Love belongs to the late-mammal circuitry—the ventral network built for connection, attunement, and co-regulation (agapē). When love holds, the threat circuits loosen their grip. The body comes back into the room. We regain access to presence, empathy, curiosity. The window widens.

Grace, in this light, is not a disembodied idea. Grace is what God’s presence feels like at the level of state. It is the body’s recognition that the bond holds. It is the slow discovery—often before we have words for it—that we have been found.

And because grace restores safety where safety was lost, it becomes the only ground on which authentic pride can grow. Grace loosens fear; love widens the river; safety allows us to interpret our own agency truthfully.

Grace makes rightly ordered shame possible. Rightly ordered shame makes authentic pride possible.

This is how theology and biology converge: grace is the restored safety in which communion becomes possible again.

The Asymmetry of Shame and Pride

Before we can speak accurately about shame and pride, we need to understand shame’s unique biological function: it’s the only innate affect whose purpose is to inhibit positive affects already underway.15 You can’t be shamed by someone you don’t care about being seen by. Shame fires when interest or joy is active and then gets interrupted—which is why it feels like sudden exposure, like falling. This is why shame always signals desire for connection, even when it feels like pure mortification. You only feel shame in relationships that matter.

Now we can speak of shame and pride with something like accuracy—not as abstractions floating in the mind, not as moral labels, but as embodied strategies the nervous system deploys in the wake of connection and rupture.

Here’s the asymmetry that changes everything: shame is instant; pride takes decades.

You can trigger shame in seconds—recall your most humiliating moment and watch your face flush, your chest tighten, your gaze drop. But try to manufacture pride on demand. Can’t be done. Pride requires years of formation in communities that teach you how to interpret your agency truthfully. Which is why therapeutic determinism (you’re just neurologically damaged”) and prosperity gospel (”speak your breakthrough into existence”) are mirror-image heresies—both trying to shortcut what can only be grown slowly, communally, rhythmically, in the width of the river.

Both promise transformation without formation, achievement without attunement, reconstruction without community. Both fail for the same reason: they’re trying to 3D-print pride when what’s needed is old-growth forestry.

Hart and Matsuba’s developmental research shows that in early childhood, pride functions as basic positive affect responding to achievement. But in adolescence and adulthood, pride becomes something more: it integrates into identity as a “highly prized end,” sustaining voluntary moral action across years of practice.16 This explains why virtue formation takes time—authentic pride doesn’t just reward single acts but becomes the stable motivational ground for a life of sustained contribution.

Shame is a biological flash—a micromoment of “something between us cracked”—arriving as rupture, a break in connection the body feels before the mind understands.17 Pride arrives slowly, only when the nervous system has regained enough safety to interpret its own agency truthfully, arriving as reconnection: “something in me is held in the bond.”18

This asymmetry doesn’t just organize your therapy sessions. It organizes your church, your politics, your entire civilization. And once you see it, you can’t unsee it. The same neurobiological dynamics that organize personal shame and pride also organize how groups understand themselves, their mission, their relationship to others. But first, we need to understand what happens when pride itself breaks down.

How the nervous system interprets agency matters crucially—and the pattern is precise.

Paul demonstrates the formula for authentic pride in 1 Corinthians 15:10: “I worked harder than any of them, though it was not I but the grace of God.” That’s internal effort (I worked) made unstable through grace attribution (not I, but grace), sustaining controllable agency (I can continue working). Authentic pride claims genuine effort while refusing to claim credit. Hubristic pride, by contrast, attributes success to stable superiority: “I accomplished this because I am inherently better than others.”

How the nervous system interprets agency matters crucially. Tracy and Robins’ research reveals pride’s three-dimensional attribution structure:

Internal vs. External: Did I accomplish this, or was it circumstances/others?

Stable vs. Unstable: Is this who I am (fixed trait) or what I did (effortful action)?

Controllable vs. Uncontrollable: Can I influence future outcomes, or was this luck/fate?

Authentic pride emerges from internal-unstable-controllable attribution: “I accomplished this through effort I can repeat.” Hubristic pride emerges from internal-stable-uncontrollable attribution: “I accomplished this because I am inherently superior.”

Paul casually demolishes the entire framework of Stoic virtue formation in one sentence: “I worked harder than any of them, though it was not I but the grace of God” (1 Cor 15:10).

Watch what he does: claims genuine agency (I worked harder), attributes success to grace (not I, but grace), sustains future effort (I can continue working). That’s internal-unstable-controllable attribution—the precise structure Tracy and Robins identify as authentic pride. Paul was doing neuroscience before neuroscience existed, because he was doing theology.

The genius is in the “though”—not “I worked and then grace helped” or “grace worked through me passively.” Paul’s claiming real effort and real dependence in the same breath. Which is exactly what the Stoics couldn’t imagine (autarkeia requires autonomous self-sufficiency) and exactly what Dominative Christianism keeps forgetting.

If your theology can’t hold genuine human agency and utter dependence on grace in the same sentence without one devouring the other, you’re not doing Christian theology—you’re smuggling Stoicism in sacramental drag.

And what we call “pride” is not one thing. The nervous system fashions two entirely different versions depending on whether shame has been healed or left festering.

Authentic pride is the embodied stance of confident belonging. It emerges only when the ventral circuitry is online, shame is rightly ordered (a semaphore, not a sentence), effort and participation are interpreted truthfully, and connection is possible. This kind of pride feels like grounded joy—not puffing up, but widening.

By contrast, hubristic pride is not the opposite of authentic pride but the nervous system’s attempt to survive disordered shame. When shame metastasizes into identity—”I am defective,” “I am unworthy,” “I am the problem”—the body recruits sympathetic broadcast energy to protect the self. Heart racing, chest tightening, jaw clenching, attention narrowing: dorsal shame covered in sympathetic armor. The mind, arriving last, misreads all this arousal as certainty, superiority, righteousness, clarity. Hubristic pride is brittle, comparative, allergic to vulnerability. It cannot be corrected with argument but can only be healed by healing the disordered shame beneath it and restoring access to the ventral circuitry where connection becomes possible again.

This is the asymmetry: pride that grows without safety is always defensive, while pride that grows within communion becomes offering—rooted, participatory, free.

This is why Christian virtue cannot be reduced to willpower. We’ve been treating pride as if willpower could manufacture what only communion produces—you might as well try to produce photosynthesis through sheer determination. Authentic pride must be formed—slowly, communally, rhythmically—in environments where the nervous system is held online by grace, truth, and presence. This is how communities keep the river wide. This is how people learn to tell the truth about themselves again. And this is why the next essay turns to the older grammar—not to escape the biology, but because the biology has finally made the wisdom visible.

Why Pride Breaks (and Why It Can Be Healed)

Tracy and Robins’ research reveals a devastating correlation: hubristic pride tracks with narcissism (r = .42-.48), while authentic pride shows no relationship with narcissism when controlling for genuine self-esteem. More tellingly, hubristic pride correlates positively with shame-proneness even while claiming superiority—the grandiose narrative defends against unhealed shame underneath.

Jessica Tracy uses Lance Armstrong as her case study in hubristic pride—and the choice is perfect. Armstrong didn’t just cheat; he constructed an entire moral universe where his cheating became heroic. He sued people who told the truth. He destroyed careers to protect the lie. And when it all collapsed, his defense was essentially: “Everyone was doing it, so my superiority was still real.”

That’s not confidence gone wrong. That’s hubristic pride in its naked form: shame wearing sympathetic armor, misread by consciousness as moral clarity. The more grandiose the claims, the more fragile the foundation. Tracy’s research shows hubristic pride tracking with narcissism while correlating positively with shame-proneness. Translation: the people who can’t stop telling you how superior they are? They’re drowning in unhealed shame, and the inflation is a life raft.

Which means when you encounter someone whose pride feels brittle, defensive, allergic to vulnerability—your first question shouldn’t be “why are they so arrogant?” but “what shame is this performance desperately covering?” The body armored in sympathetic arousal. The mind misreading survival as strength. The story constructing superiority from terror.

And here’s what makes this pattern so stubborn: you can’t argue someone out of hubristic pride any more than you can shame someone out of shame. Both operate at the level of nervous system state, not narrative content. The only thing that heals disordered shame is the slow work of co-regulation in communities where grace, truth, and presence hold people online long enough for new patterns to form.

Which is why it matters that most churches are organized around maintaining disordered shame disguised as humility. We’ve baptized Stoic self-sufficiency, called it sanctification, and wonder why people can’t form authentic pride. You can’t produce ventral safety in communities organized around sympathetic threat. You can’t form rightly-ordered pride in environments that weaponize shame into moral leverage. The body knows the difference between incarnational presence and domination dressed up in theological language.

This explains why Dominative Christianity appears simultaneously arrogant and fragile. The superiority claims (”real America,” “God’s chosen people”) aren’t grounded in genuine contribution but function as defensive shields against terror of inadequacy. Any challenge threatens the entire structure because shame remains unmetabolized beneath the inflation.

The body knows what the mind denies. Hubristic pride activates sympathetic defense systems—heart racing, chest tightening, threat vigilance—not the ventral safety of authentic pride. The nervous system treats superiority claims as ongoing emergency requiring constant maintenance. This is why Dominative Christianist communities cannot rest, cannot celebrate others’ flourishing, cannot tolerate complexity or failure. The defensive structure demands total vigilance.

The Determinism Trap

I spent years believing that damage done early enough was damage done for good. The formation patterns I absorbed—the codependent caretaking, the hypervigilance around others’ dysregulation, the belief that my worth depended on successfully managing other people’s nervous systems—felt like grooves carved too deep to escape. If shame got in at the firmware level, if the nervous system learned its patterns in infancy, what hope was there for those of us who spent decades building lives on faulty foundations?

Here’s what makes shame so devastating: it’s the only innate affect whose biological function is to inhibit positive affects already underway.19 You can’t be shamed by someone you don’t care about being seen by. Shame fires when interest or joy is active and then gets interrupted. This is why shame feels like sudden exposure, like falling—because neurobiologically, that’s exactly what’s happening. Which means shame always signals desire for connection, even when it feels like pure mortification. You only feel shame in relationships that matter.

Then I discovered neuroplasticity. Not as technique or self-help strategy, but as scientific ground for something I couldn’t have believed otherwise: we’re not permanently stuck with the patterns formed in our childhood. The brain retains capacity for change throughout life.20 Adult attachment relationships can literally enable healing of childhood attachment wounds—not by erasing what happened, but by providing the relational safety that allows new neural pathways to form alongside old ones, gradually shifting default patterns from threat-based to connection-based.

But here’s what stopped me: neuroplastic change requires exactly what Wells describes—sustained “being with” across years, not breakthrough moments. The timeline matters. Acute stress responses can normalize within months of consistent safety. But deeply embedded attachment patterns formed in the first three years typically require three to five years of sustained secure attachment to significantly reorganize.2122 The prosperity gospel wants instant transformation. Therapeutic culture wants weekend breakthroughs. Both miss what the biology reveals: healing damaged neural networks takes years of sustained safe presence, not moments of insight.

Which brings me to something I’ve been seeing more clearly the longer I stay in this work. The therapeutic determinism that settled into our culture over the last few decades—the belief that certain patterns represent permanent, unfixable conditions—creates a tragic bind for those living with shame-based attachment disorders.

The spectrum is broader than most realize: substance addiction and alcoholism, certainly, but also perfectionism, eating disorders, relationship addiction, workaholism, compulsive spending. Borderline personality disorder, complex PTSD, narcissistic patterns—these emerge most directly from shame-based attachment trauma. Obsessive-compulsive disorders, generalized anxiety, some depressions—these may develop through different pathways but become entangled with shame secondarily.

What they share: nervous systems that learned early that safety requires constant vigilance, that attachment threatens annihilation, that shame signals permanent defect rather than temporary rupture requiring repair.

When these patterns get framed as ontological defects rather than adaptive responses to early relational trauma, the diagnosis itself becomes a shame trigger. And Nathanson’s research predicts what happens next: the Compass of Shame activates.

Some respond through Attack Other—but not against distant clinicians or abstract frameworks. The attack turns toward those closest, toward the very people offering sustained presence. Family members who stay. Friends who keep showing up. Communities attempting to embody Being With. Because when you’ve internalized the belief that presence means eventual abandonment, when every attachment experience has taught that connection will turn to contempt, the offering of presence itself registers as threat. The nervous system reads sustained care as the prelude to betrayal and activates defense preemptively—pushing away precisely what it most needs.

Others turn to Attack Self—spiraling into self-loathing that confirms their worst fears about being fundamentally defective. Still others choose Withdrawal—disappearing from families, from friendships, from ecclesial communities, protecting themselves through distance from the very bonds of affection that could enable healing. Or Avoidance—remaining physically present while refusing genuine participation, performing connection while patterns continue unchanged beneath the surface.

Each response makes neurobiological sense. When accepting reality about your patterns feels like consenting to permanent broken status—when diagnosis carries the implicit message “you are ontologically defective and should be cast aside”—the nervous system does what nervous systems do when faced with existential threat: it activates defense. And communities formed to practice Being With become the very sites where the compass spins most dangerously, not because these communities are failing but because sustained presence feels unbearable to those who have learned that presence always ends in abandonment.

This is where the reframing matters: Toxic shame says, “I am fundamentally flawed; something about my essential being is wrong; I should be cast aside.” Rightly-ordered shame says, “I developed protective patterns in unsafe environments; these patterns made sense given what I faced; they’re not who I am but how I learned to survive; and they can change through sustained safe connection.”

The difference isn’t semantic. It’s the difference between “I am broken” and “I am hurt.” One demands hiding; the other invites healing. One locates the problem in your essence; the other locates it in your early environment and your nervous system’s brilliant adaptation to danger. One makes change impossible; the other makes change creaturely—slow, embodied, relational, real.

This is perhaps the cruelest consequence of therapeutic determinism. It prevents participation in the very communities where neuroplastic healing could occur. Because what the neuroscience reveals is that authentic pride—the kind rooted in genuine effort rather than comparative superiority—requires specific communal conditions: Environments where effort is celebrated without exploitation. Where agency is interpreted truthfully. Where shame can be received without contempt. Where people are held in sustained bonds of affection that widen windows of tolerance rather than narrowing them.

These are not clinical conditions. These are ecclesial conditions. Family conditions. The conditions of ordinary communities that practice incarnational presence. And here’s what Cozolino’s research demonstrates: these same communal conditions literally enable the reorganization of traumatized nervous systems.23 The patterns formed in early relational danger are not ontological defects but adaptive formations—nervous systems that organized themselves around survival when attachment meant threat. Which means the patterns are not identity. And patterns, unlike identity, can change.

But change requires what Wells calls Being With—not working for, not strategic intervention, but sustained incarnational presence.24 The kind that lends regulated steadiness without demanding reciprocal performance. The kind that stays through dysregulation without absorbing it or fleeing from it. The kind that says, through a thousand ordinary interactions across years: You’re not permanently broken. You’re hurt. And hurt can heal.

This is where Paul’s word cuts through the therapeutic determinism: “See, I am making all things new.” Not erasing what was. Not pretending the damage didn’t happen. But making new—transformation that respects the reality of formation while refusing to grant it permanent ontological status.

You are not your nervous system’s early adaptations. You are not your shame’s diagnosis of your identity. You are not the patterns that once kept you alive when genuine connection threatened survival. Those patterns made sense. They may have saved you. But they’re not ultimate. They’re not ontological. They’re not you.

And in communities that practice Being With—communities where grace, truth, and presence hold people online long enough for neuroplastic change to occur—those patterns can gradually give way to something closer to what you were always meant to be.

This is gospel. Not spiritual technique layered over unchanged biology, but the biology itself revealing the shape of redemption. Hurt can heal. Patterns can change. Pride can form rightly. And the river can widen again.

Where Pride Actually Grows

If shame is firmware and pride is software, then the question of identity shifts: who am I when my patterns are responses to formation rather than expressions of essence? This is where neuroscience and theology converge in ways that make each discipline more intelligible.

Here’s what makes this research theologically profound: the attribution structure that produces authentic pride maps almost perfectly onto what Douglas Campbell calls “participatory righteousness”—the apocalyptic Pauline framework where genuine human agency operates within grace-enabled participation in creative fellowship with God and the created order. You contribute genuinely (internal) through received capacity (unstable) that you can exercise but didn’t create (controllable participation in gift).

The contractual theology that Campbell critiques produces exactly the hubristic attribution pattern: righteousness as achieved status (internal-stable) secured through correct belief or performance (autonomous control). This is why contractual frameworks, despite condemning pride, create its conditions. When salvation depends on securing permanent status through correct performance, some respond with chronic anxiety about adequacy—while others respond with defensive inflation to mask that same anxiety. Both are symptoms of the same diseased framework.

In contrast, participatory frameworks enable authentic pride: you genuinely contribute to God’s redemptive work (internal), but the capacity to contribute is gifted rather than inherent (unstable), and you can exercise this capacity through practices that form you (controllable participation). This is Aquinas’s magnanimity—rightly ordered pride in participating in divinely enabled goods. This is Aristotle’s proper self-love—the grounded confidence that comes from being rightly ordered toward the good.

And this is why authentic pride requires formation in communities of character—contexts where agency is interpreted truthfully. You can’t will yourself into authentic pride any more than you can will your nervous system out of defense activation. Both require environments that hold you truthfully while your patterns reorganize.

MacIntyre’s account of practices illuminates this: virtues like authentic pride are formed through participation in communities whose traditions maintain coherent narratives about what constitutes genuine contribution. You learn authentic pride the way jazz musicians learn improvisation—through years of practice within communities that celebrate genuine effort while maintaining standards, that welcome failure as material for learning, that honor individual contribution while serving the ensemble’s flourishing.

This is formation, not construction. You don’t build pride; you’re formed into it through participation in communities that practice truthful interpretation of agency. And formation, Bowlin demonstrates, is deeply contingent—dependent on communities, practices, and providential circumstances beyond individual control. Which means authentic pride is simultaneously genuine achievement and received gift.

The jazz ensemble offers a fitting image: musicians take authentic pride in individual development (hours of practice, technical mastery) while that pride emerges from and serves the communal performance. No one claims superiority; everyone celebrates contribution. The pride that sustains practice is the same pride that enables generous participation.

This is why Christian virtue cannot be reduced to willpower. Authentic pride must be formed—slowly, communally, rhythmically—in environments where the nervous system is held online by grace, truth, and presence.

Being With: The Incarnational Horizon

Theologians sometimes talk as if communion were an idea, a doctrine to be affirmed. But the nervous system tells a simpler truth: connection is creaturely. It has a physiology. It has a posture. It has a feel.

When the church speaks of incarnation, of God choosing to be with us in Jesus, it is naming something that is not merely spiritual but bodily. Presence is not an abstraction. It is what happens when the ventral circuitry stays online long enough for two lives to meet without fear.

This is what Sam Wells means by Being With. It is not heroic activism or strategic influence. It is the practice of staying present—of lending our regulated selves so that others can find safety again. Being With is what happens when grace, truth, and presence hold a community’s nervous system online.

The Johannine language is precise: Jesus came “full of grace and truth” (John 1:14). Not grace or truth, as if we must choose between acceptance and honesty. Not grace then truth, as if we earn confrontation after proving our loyalty. Grace and truth, integrated—the capacity to provide regulated presence (grace as safety signal) joined with truthful interpretation (truth as coherent narrative).

This is theological co-regulation: Jesus’s presence signals safety strongly enough that truthful confrontation doesn’t trigger defensive collapse. Grace isn’t permission to ignore truth, and truth isn’t condemnation that forecloses grace. They’re integrated in incarnate presence—the same integration the nervous system requires for healing.

Wells distinguishes Being With from four alternatives that modern Christianity often confuses with incarnational presence:

Working For: Solving others’ problems while maintaining power differential

Working With: Strategic partnership that remains instrumental

Being For: Advocacy from distance

Being Alongside: Companionship that avoids hard truth

Being With combines presence (entering another’s reality) and truthfulness (maintaining honest speech) in ways that require surrendering control without abandoning responsibility. This posture mirrors Jesus’s own ministry: he doesn’t fix people’s problems from above but enters their conditions—table fellowship with sinners, touching lepers, weeping at tombs—while speaking truth that invites transformation rather than shaming into compliance.

Neurobiologically, Being With describes what Porges would call maintaining ventral vagal presence through sustained connection: the regulated person lending their regulation to the dysregulated person through embodied proximity, calm tone, soft face, and patient presence that signals safety strongly enough for the other’s defensive circuits to gradually stand down.

This isn’t technique but theological commitment: we practice Being With because God first practiced it with us in Jesus, entering our dysregulated existence and remaining present until co-regulation could occur—incarnation, ministry, cross, resurrection, ongoing presence through Spirit and Body.

But here’s where the eschatological horizon opens: Being With is not merely therapeutic intervention aimed at individual healing. It’s participation in the new creation already breaking into this age. When Paul writes “See, I am making all things new” (Revelation 21:5), he’s not describing distant future but present reality—the kingdom invading history through communities that embody incarnational presence.

This is Zizioulas’s insight: being itself is communion. We don’t have stable “selves” that then enter relationships; we become persons through relationships in which we participate. The divine Persons—Father, Son, Spirit—are constituted as persons through their mutual relations. Created persons image this Trinitarian structure: we exist not as isolated egos but as ec-static reality, existing outside ourselves in communion with God and others.

Which means authentic pride—rightly ordered self-regard—can only emerge through participation in truthful relationships. Hubristic pride attempts the impossible: autonomous self-constitution through achieved superiority. But since being is communion, the attempt to exist autonomously produces not selfhood but dissolution.

This is why communities that practice Being With are not merely therapeutic spaces but eschatological signs—glimpses of what human existence looks like when organized around communion rather than domination. When shame is received without contempt. When failure becomes material for further formation. When agency is interpreted truthfully—genuine contribution enabled by grace. When the river stays wide.

Campbell’s participatory righteousness finds its proper horizon here: participation isn’t instrumental (doing things to achieve status) but ontological (existing in communion). And within this participatory existence, authentic pride becomes possible—not pride in autonomous achievement but pride in genuine contribution to the communal work God is doing.

The neuroscience and the theology speak the same truth from different angles: healing happens in relationship. Formation happens in community. Pride forms rightly in environments where grace and truth hold people online long enough for patterns to reorganize around connection rather than defense.

Communities that practice Being With aren’t therapeutic programs optimizing neuroplasticity. They’re participating in what God is already doing: making all things new. The convergence of neuroplastic healing and spiritual formation isn’t happy accident—it’s how incarnation works. God didn’t create nervous systems that could theoretically heal under ideal conditions. God created nervous systems designed for co-regulation, brains wired for attachment, affects that fire to call us back toward communion. This is the design.

Which means the prosperity gospel and therapeutic determinism aren’t just pastorally unhelpful or scientifically naive. (Offering theological Photoshop when bodies require actual healing—performance spirituality for people allergic to embodiment.) They’re theological heresies that deny creation’s goodness. Prosperity gospel says bodies don’t matter (just achieve through faith). Therapeutic determinism says bodies are all that matter (you’re just your neurology). Both deny that bodies can be redeemed—one through spiritual bypass, one through biological fatalism.

Against both, the older Christian claim: bodies that learned threat can learn safety. Nervous systems that organized around defense can reorganize around connection. Hurt can heal. Patterns can change. Pride can form rightly. Not because we’re strong enough to change ourselves, but because we’re held in bonds of affection strong enough to bear the weight of our formation while new patterns grow.

This isn’t wishful spirituality imposed on resistant biology. This is the biology—nervous systems designed for co-regulation, brains that reorganize through sustained safe attachment, affects that fire to call us back toward communion. And this is the gospel—not escape from embodied existence but its redemption. Not transcendence of our creaturely limits but their transformation. Not freedom from our biology but freedom through it, as the body that learned threat becomes the body that learns safety.

A God who meets us not above our biology but within it. A salvation that doesn’t bypass the body but heals it. A pride that doesn’t escape embodiment but finally arrives in it, grateful.

And this is where the next essays turn—to see how these patterns play out in the specific formations and deformations of contemporary Christianity. Because once you see the asymmetry, once you understand how shame operates at the firmware level while pride functions as constructed software, once you recognize that healing requires sustained Being With rather than heroic intervention or instant transformation...

Then you can’t unsee the ways both MAGA Christianism and Providential Identitarianism have built their entire edifices on faulty foundations, trying to construct pride over unmetabolized shame, demanding performance from nervous systems organized around defense, narrowing the river when what’s needed is its widening.

But that reckoning comes later. For now, this: You are not your patterns. Your patterns are not your identity. And in communities that practice Being With, those patterns can gradually give way to something closer to what you were always meant to be.

The river can widen. The body can learn safety. Pride can form rightly. All things can be made new.

Coda: A Note on Rhythm

Several of you have shared that these essays ask something of you — not just attention, but emotional space. I feel that too. This work isn’t light; it’s slow, layered, the kind of writing we metabolize rather than skim.

To honor that, and to make this journey companionable rather than rushed, I’m shifting to a gentle, sustainable cadence: every other Friday morning, you’ll receive the next movement in the Jazz, Shame, and Being With series.

My hope is that this gives each essay room to breathe — for you to sit with it, return to it, and let it do its work without pressure. I’m grateful to be walking this long arc with you.

With affection and steady presence,

Craig

ENDNOTES

A NOTE ON THESE NOTES

If you’re the kind of person (like me) who reads endnotes (and bless you if you are), these are the research sources and technical explanations you’ll actually find useful. I’ve kept only the citations that directly support the essay’s main claims and the concepts that genuinely need clarification.

For the full scholarly apparatus (71 citations), there’s a complete version available—but that’s for people writing dissertations, not for reading on your phone.

Neuroception is the process where your nervous system evaluates risk without conscious awareness.

Before you consciously think “that person is safe,” your nervous system has already decided and responded. You notice the decision after it’s been made—when you realize you’re leaning away or your shoulders are tense.

This is why telling someone “you’re safe, don’t worry” often doesn’t work. Their conscious mind might agree, but their neuroception is screaming “THREAT!” and that signal overrides rational assessment.

Porges, S. W. The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, and Self-Regulation (New York: W. W. Norton, 2011), 11–29.

Jessica Tracy and Richard Robins published the landmark study in 2007 that said: “Hey, we’ve been treating ‘pride’ like it’s one thing, but it’s actually two completely different experiences.”

There’s authentic pride—that grounded feeling of “I worked hard and accomplished something meaningful.” And hubristic pride—that brittle, defensive “I’m better than you” feeling that requires constant validation.

The kicker? Authentic pride correlates with genuine self-esteem and prosocial behavior. Hubristic pride correlates with narcissism, aggression, and—wait for it—shame-proneness. The most grandiose people are often the most shame-filled underneath.

Tracy, J. L., & Robins, R. W. (2007). “The psychological structure of pride: A tale of two facets.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(3), 506–525.

Louis Cozolino’s synthesis demonstrates that human neurobiology is fundamentally relational: “people, like neurons, excite, interconnect, and link together to create relationships.”

The developing brain literally requires other brains for healthy maturation. You can’t develop a healthy nervous system in isolation.

The hope: secure relationships can reshape neural architecture even after severe relational trauma. Neural plasticity remains available throughout life.

But reshaping happens through relationship, not achievement or willpower. You need sustained, safe connection with regulated others.

Cozolino, L. The Neuroscience of Human Relationships, 2nd ed. (New York: W. W. Norton, 2014).

Stephen Porges’ Polyvagal Theory maps three nervous system states that are always all operating simultaneously, just competing for dominance:

Ventral vagal (safety/social engagement): Connection, play, learning. Your face is expressive, voice has warmth, you can make eye contact.

Sympathetic (mobilization): Fight-or-flight. Could be anxiety, could be excitement, depends on context.

Dorsal vagal (immobilization): Freeze, shutdown, collapse. Conservation mode when threat is overwhelming.

When you’re anxious, all three are still active—your sympathetic has just won the competition for dominance. You’re not trying to turn systems on or off; you’re trying to strengthen ventral vagal capacity.

Porges, S. W. The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, and Self-Regulation (New York: W. W. Norton, 2011).

Allan Schore’s research shows why achievement-based approaches to healing shame fail structurally.

Shame is subcortical—it fires in milliseconds through the amygdala and limbic system before conscious processing. That’s the brainstem and midbrain level (”firmware”).

Achievement is cortical—it requires conscious processing, narrative construction, attribution (”software”).

Trying to heal shame through achievement is like trying to fix firmware problems with software updates. You’re working at the wrong level of the system.

Shame heals through right-brain-to-right-brain attunement and co-regulation—regulated presence that gradually shifts your nervous system from threat to safety.

Schore, A. N. Affect Dysregulation and Disorders of the Self (New York: W. W. Norton, 2003), 201–246.

The social engagement system is how mammals use social connection to regulate each other’s nervous systems.

It involves: facial expression, vocal prosody (rhythm and tone of speech), head turning, and listening (middle ear muscles tuned to human vocal frequencies).

When your ventral vagal system is active, your face is animated, voice has warmth, you make eye contact. When you’re in sympathetic or dorsal mode, all this shuts down—face flattens, voice goes monotone, eye contact feels threatening.

This is why video calls are exhausting. You’re trying to read social engagement signals through a screen with lag and artifacts, making your nervous system work overtime.

Porges, The Polyvagal Theory, 121–129, 203–222.

Porges, The Polyvagal Theory, 121–129, 203–222.

Dan Siegel’s “window of tolerance” describes the range of arousal where you can function effectively—not too activated, not too shut down.

Within the window: You can think clearly, connect, respond flexibly. (Ventral vagal dominance)

Above the window: Too activated—anxious, panicked, aggressive. (Sympathetic dominance)

Below the window: Too shut down—numb, dissociated, collapsed. (Dorsal dominance)

Trauma doesn’t just dysregulate you in the moment. It narrows your window over time. Things that wouldn’t have triggered you before now push you out faster.

The good news: Safe relationships can gradually expand your window through co-regulation.

Siegel, D. J. The Developing Mind: How Relationships and the Brain Interact to Shape Who We Are, 2nd ed. (New York: Guilford Press, 2012), 353–355.

Co-regulation is where one regulated nervous system literally helps another nervous system regulate. It’s not metaphorical—it’s biological.

When you’re dysregulated, you can’t just think your way back to safety. But being near someone who is regulated—whose calm presence signals safety—can begin shifting your nervous system back toward social engagement.

This happens through vocal tone, facial expression, body posture, breathing rhythm. The regulated person’s state provides cues that help your neuroception shift from threat to safety.

Here’s the thing: You can’t fake this. Your nervous system broadcasts your actual state. If you’re anxious but trying to act calm, people pick up the anxiety underneath.

Porges, The Polyvagal Theory, 203–222, 251–264.

Neurons that fire together wire together” is Siegel’s way of describing how repeated neural activation patterns become established pathways.

The brain you have at 40 isn’t locked in by attachment patterns formed at 4. Neural wiring can change throughout life through new relational experiences.

But—crucially—the change happens through sustained, safe relationship, not willpower or achievement. You need repeated experiences of regulated presence with others.

This is why church communities that practice actual “being with” matter neurobiologically. They’re literally rewiring neural architecture through sustained co-regulation.

Siegel, The Developing Mind, 25–28, 285–293.

Porges, The Polyvagal Theory, 121–129, 203–222

Porges, The Polyvagal Theory, 203–222, 251–264

Schore, A. N. Affect Dysregulation and Disorders of the Self (New York: W. W. Norton, 2003), 201–246.

Sam Wells’ theology of “being with” provides the framework for understanding incarnation as co-regulation.

God doesn’t “work on” humanity’s problems from a distance. God “is with” humanity—entering our dysregulated existence (incarnation), staying present through it (ministry), enduring our worst dysregulation while maintaining connection (cross), continuing presence (resurrection, Spirit, Body).

This is how co-regulation actually works. The regulated presence stays with the dysregulated presence until co-regulation can occur.

Jesus heals through sustained, embodied presence—touching, speaking, looking, staying. This is right-brain-to-right-brain communication providing ventral vagal safety signals.

The church continues this work through practicing sustained, embodied being-with that provides the co-regulation context where healing can occur.

Wells, S. A Nazareth Manifesto: Being with God (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2015); Learning to Dream Again: Rediscovering the Heart of God (Norwich: Canterbury Press, 2013).

Silvan Tomkins’ crucial insight: Shame is specifically the affect that inhibits positive affect—particularly interest and enjoyment.

You’re engaged with something (interest) or taking pleasure in something (enjoyment), and then shame fires, suddenly cutting off the positive affect.

This explains why shame is so disorienting. Other negative affects have clear external triggers—you’re angry atsomething, afraid of something. But shame fires when your own positive engagement is interrupted, creating the sense that something about you is wrong.

For pride formation: shame can interrupt emerging authentic pride before it develops. You start feeling good about a contribution, shame fires (”who do you think you are?”), and the pride gets cut off.

Tomkins, S. S. Affect Imagery Consciousness, 4 vols. (New York: Springer, 1962-1992); summarized in Nathanson, Shame and Pride, 131-157.

Daniel Hart and Kyle Matsuba’s longitudinal research tracked how pride changes across development.

In early childhood (ages 3-7), pride is basic pleasure in accomplishment—the joy of building a block tower or riding a bike.

But in adolescence and adulthood, pride becomes integrated into identity as what they call “a highly prized end”—the motivational ground for sustained moral action across years.

This explains why virtue formation takes time. Authentic pride doesn’t just reward single acts; it becomes the stable foundation for a life of continued contribution.

Hart, D., & Matsuba, M. K. “The Development of Pride and Moral Life,” in The Self-Conscious Emotions: Theory and Research, ed. Tracy, Robins, & Tangney (New York: Guilford Press, 2007), 114–132.

Donald Nathanson’s work on shame as a biological affect was foundational for me. An affect is an instant physiological flash that fires before thought or interpretation.

Shame is one of nine hardwired affects that signal broken connection. It’s not a thought or belief about yourself. It’s a biological signal—like pain, but for relational rupture.

This is why telling someone “you shouldn’t feel ashamed” doesn’t work. You might as well tell them “you shouldn’t feel pain.” The signal is pre-cognitive.

Nathanson, D. L. Shame and Pride: Affect, Sex, and the Birth of the Self (New York: W. W. Norton, 1992).

Pride doesn’t just appear randomly. It emerges based on how you explain your success to yourself.

Authentic pride: “I succeeded because I worked hard, and I can do it again.” (Internal-unstable-controllable attribution)

Hubristic pride: “I succeeded because I’m naturally superior.” (Internal-stable-uncontrollable attribution)

Tracy and Robins’ research reveals pride’s three-dimensional attribution structure:

Internal vs. External: Did I accomplish this, or was it circumstances/others?

Stable vs. Unstable: Is this who I am (fixed trait) or what I did (effortful action)?

Controllable vs. Uncontrollable: Can I influence future outcomes, or was this luck/fate?

This explains why different people handle failure so differently. Authentic pride thinks: “I need to work harder or try differently.” Hubristic pride thinks: “This threatens my entire identity.”

Tracy & Robins, “The psychological structure of pride,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 92, no. 3 (2007): 520–522.

Tomkins, S. S. Affect Imagery Consciousness, 4 vols. (New York: Springer, 1962-1992); summarized in Nathanson, Shame and Pride, 131-157.

Siegel, The Developing Mind, 25–28, 285–293.

Louis Cozolino explains how the nervous system communicates through three messenger systems at different speeds:

Neural transmission (milliseconds): Electrical signals. Fast, direct, immediate.

Hormonal signaling (seconds to minutes): Chemical messengers through bloodstream. Slower, more sustained.

Genetic expression (hours to days): Which genes activate/deactivate. Slowest, most enduring.

Quick interventions might shift neural transmission (breathing exercises help right now). But transforming hormonal patterns requires weeks of sustained practice. Reshaping genetic expression requires months to years.

This is the neuroscience underneath “the long formation.” Real transformation doesn’t happen in a weekend workshop.

Cozolino, L. The Neuroscience of Human Relationships, 2nd ed. (New York: W. W. Norton, 2014), 49–67, 307–320.

Stanley Hauerwas’ insistence on “the long formation” is neurobiologically grounded.

Virtue isn’t acquired through decisions or insight. It develops through sustained practice in communities over years—practice that gradually reshapes desire.

Neurobiologically: Neural pathways (milliseconds) → hormonal patterns (weeks/months) → genetic expression (years). Real transformation requires all three levels.

Quick interventions might shift neural firing temporarily. But reshaping hormonal regulation and genetic expression requires sustained practice over years.

Church isn’t a weekend workshop. It’s sustained participation over decades in communities practicing specific ways of being with each other.

Hauerwas, S. The Peaceable Kingdom (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1983); A Community of Character(Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1981).

Siegel, The Developing Mind, 25–28, 285–293.

Wells, S. A Nazareth Manifesto: Being with God (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2015); Learning to Dream Again: Rediscovering the Heart of God (Norwich: Canterbury Press, 2013).